It is such a simple question but a difficult one to answer. The simple answer, “I am a psychiatrist,” leaves me feeling defensive and, unfortunately, ashamed. I am used to the awkward laugh. Pause. And then some version of, “Gosh, I should come see you,” or even more often, “My wife (or some other significant other –fill in the blank) should make an appointment.” Wink. Wink. Ha. Ha. (Note: this is rarely stated if the Other is standing right there, but if She is, the laughter is louder to make it clear it is a joke—REALLY, I swear!)

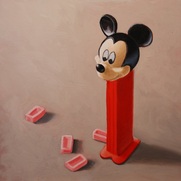

That is not the problem – for me anyways. My defensiveness and shame arise because I feel the need to make clear that I am not one of THOSE psychiatrists-- the ones who meet with you for 15 to 30 minutes, label you with one of the ever expanding list of pathologies defined by checklists in the psychiatric “bible”, the DSM-V, then simply hand over a prescription, sometimes two, as casually as handing over a Pez candy out of a Mickey Mouse dispenser. In fact, a growing body of research contends that giving you a Pez, with the assurance that this will work for you, is likely to work just as well as the actual antidepressant you will be given, minus the potential short and long term side effects of a “real” pill.

Few psychiatrists have read these articles, even though they have been published in top journals like the New England Journal of Medicine. They are not to blame, as I assure you, these articles are not exactly part of required reading in psychiatry residencies—at least not in mine! Psychiatrists are, after all, no different than anyone we may treat, in that we are apt to avoid the unfamiliar and those things that do not fit into our already established dogma of beliefs. Although we may be quick to spot this tendency in others, we may be less likely to see it in ourselves!

Many of the “dysfunctions” you may be diagnosed with used to be considered “normal”, like, say, grieving for the loss of a spouse or a child for more than a couple weeks; or feeling anxious when trying to meet too many needs at work and at home with no time to oneself; or being diagnosed with cancer and feeling overwhelmed; or being angry and not able to focus on your work at school when your dad has been deployed to some war torn country; or just a whole host of other normal responses to life’s losses and challenges.

The psychiatric community and their friends, the pharmaceutical industry, have conveniently determined, however, that we humans should not have to suffer with emotions like grief or anxiety, and that despite living in a world constantly vying for our attention 24 hours a day with cable TV updates on every bad thing happening everywhere in the world, and Facebook and Twitter feeds on everything happening to everyone you know, that somehow we should be able to focus and concentrate at all times or take a pill so that we can do so more easily.

(In fact, your psychiatrist may be prescribed a pill if you had a difficult time focusing on that last very long sentence!)

So with your newly acquired diagnosis, you will be sent on your way with your script and a plan to follow up in a month to see if that pill has “solved” the presenting problem. At the next visit you will be evaluated for how you are doing. If you are “better” it will be assumed it was because of the medication, or medications, bestowed upon you with great authority. If you happen to be worse it will be assumed it is because you need a higher dose or an additional medication-- often to contend with the side effects of the first-- or perhaps you didn’t take it correctly or “compliantly” enough, and sometimes because, well, why not? Two Pez of different flavors must be better than one, right?

Actually, not. Despite all the talk about evidence based medicine, research has consistently found that two antidepressants do not confer benefits over one, but do significantly increase the risk of side effects. Yet most psychiatrists continue to hand out multiple medications because with only 15 minutes to assess you there’s not much time to explore WHY you might be having these symptoms. It is easier to write if off to a “chemical imbalance.” Seeking the CAUSE for the imbalance and exploring what in this person’s life may need balancing requires more time and attention.

Although there is ample evidence of frequent side effects from medications, it is rarely assumed that someone might be doing worse BECAUSE of the medication. A recent study revealed that over 900,000 emergency department visits a year are secondary to receiving a psychiatric or sleep medication. The conclusion to this study was that this is a small number of people given the 28.5 million people on psychiatric medications, although there was an acknowledgment that this is a gross underestimation as most people suffering from side effects never visit the emergency department.

In fact it is those people who do not visit the emergency department that often appear in my office because they have heard I am a “holistic psychiatrist.” “A what?” you may ask with a puzzled look. It is that response that causes me to pause before using that phrase to answer the question of what I do for a living. This answer usually requires a longer explanation.

I explain that I most often use my prescriptive powers to help people get off their medications. People seek me out because they either don’t want to be started on medications, and intuitively realize there might be other healthier solutions to their depression and/ or anxiety besides taking a pill; or they were recently started on medications and whenever they attempt to explain to their physician that the medications are making them feel worse, they simply get written off as being anxious and started on a medication for their anxiety; or they have been on medications for decades and nothing has ever worked and they have given up hope in finding a cure in a pill.

Regardless of which particular reason they arrive, my approach is pretty much the same. I am not particularly interested in which diagnostic code I can check off and match with a medication. I am interested in their life, their story, the whole person sitting in front of me --with no computer between us. Of course, I want to know about their symptoms and their particular flavor and experience of depression or anxiety or psychosis or mania with which they present, but more importantly I want to know about what was going on in their life when the symptoms began, what effect those symptoms had on their life then and since; what fears they now carry about any of those symptoms reappearing; what they believe about their “illness” and what is says about them; what their family believes about the illness and what it says about them. I want to know what they find meaningful in their lives, what they believe in spiritually, what sort of balance they have in their life between work and play. I want to know what they do to relax. I want to know about their relationships and the support they receive or don’t receive. I want to know what they eat, what they do for exercise, what they do for play, what brings them joy. I want to know about their emotional life – what they are allowed and willing to express and how they do that, and what emotions are kept silent and buried, stewing beneath the surface.

These aren’t unique questions. They are the questions psychiatrists always used to ask before their jobs got reduced to 15 minute medication checks. In fact, these are questions I was trained to ask as a resident, but then was not given enough time to ask when I became an attending at the same hospital system. As an employee getting enough RVUs -- which means seeing more people for less amounts of time so the hospital can make more money-- was and is considered more important than taking time to listen and be present with patients in order to facilitate healing. Time, listening and presence are at the core of all healing modalities, but they don’t earn revenue.

So after gathering this information, I attempt to weave the narrative of their lives together with the latest research on the amazing neuroplasticity of the brain, and how we all have the capacity to rewire our brains to better focus and concentrate and manage stress and emotions using tools like meditation, breathing, biofeedback, guided imagery, hypnotherapy and others. Mind you, these are not tools I learned in medical school or residency, which is a shame given the vast amount of research accrued demonstrating their efficacy. There are, unfortunately, no attractive former cheerleaders turned pharmaceutical reps visiting weekly with a free lunch and shiny expensive brochures of smiley, happy people advocating for these free (no patents and padded pocket books available!) but empowering and effective techniques.

I educate my patients about emotions and their intrinsic value in guiding us forward on our life paths and the dangers of blocking or numbing our emotions whether it’s with drugs, food, alcohol, work, distraction, or prescribed medications, like antidepressants and anxiolytics. I attempt to plant a seed to reframe their moods and emotions as normal messengers alerting us when life is out of balance, rather than pathologizing them as a threat to be feared and avoided. For those on antidepressants or considering them, I discuss the research showing the long term psychological consequences of their use including feeling emotionally numb, caring less for other people and feeling fewer positive feelings, as well as repeated studies demonstrating that in cases of mild and moderate depression antidepressants are no more effective than a placebo.

For those interested I debunk the mythology of neurochemical imbalances and educate them about a growing body of research, still largely ignored by the psychiatric community, that suggests that depression, along with 80-90% of chronic disease, is more likely a result of inflammation, which is primarily caused by stress. If stress is a primary cause of what we call mental (and physical) illness, wouldn’t it make more sense and be far more empowering to learn how to manage stress ourselves rather than cover up its emotional effects with a medication?

Learning self care skills empowers someone for life rather than making one dependent upon a doctor and his or her prescription pad for ones well being. It shifts us out of a mindset that we have been dealt a bad genetic card into the recognition that most mental and physical illness is more a matter of epigenetics—the interplay of our genes with the environment, which includes our beliefs, thoughts, emotions, behaviors, diets, and lifestyle—in other words CHANGEABLE factors. If this is true, as an ever growing body of research indicates, then we are not passive players doomed to a lifetime of pills but active participants in our own healing (or wounding). By collaborating in our healing process, are we not removing the sense of powerlessness and helplessness which fuels anxiety and depression, replacing it with a greater sense of control and self-efficacy, which research clearly demonstrates reduces the risk of mental illness?

So I have started this blog to break my self-imposed silence about my views on the state of psychiatry (and medicine in general). For years I have been listening to colleagues discuss patients and their medications. “I have tried Zoloft, Effexor, Cymbalta, Abilify, Risperdal, Ativan and Depakote and nothing has worked. Can you think of any other medications I might try?” I listened and suggested that, perhaps, medication is not the answer, as the person walked away with a puzzled, even hurt look. (I wish I were making up that conversation, but I am not.) Please don’t get me wrong. These are good people (most, anyways) with good intentions, who are practicing medicine the way we were trained to practice medicine in medical school and residency and within the confines of a medical and insurance system that only pays for shorter and shorter visits.

What I have learned since med school and residency, however, is that there are other safer, equally effective and more empowering ways to manage depression and anxiety and often even what we call bipolar and schizophrenia. I have come to these conclusions based not only on my own experiences as a doctor –and patient—but also based on massive amounts of research, that sometimes manages to get published in the big medical journals funded by glossy pharmaceutical ads, but still gets overlooked, because it does not conform with the dogmas of the profession that create blinders difficult to see past.

Also, please understand that I am not saying medication should never be used. There are times and places for medications, but they should be used judiciously and wisely and not handed out like candy for every problem and every “negative” emotion, but reserved for use only after other safer and more self empowering options have already been tried.

Fortunately a growing number of physicians—and patients-- are speaking up and out about their dissatisfaction with psychiatric (and medical) care. I feel compelled to add my own voice to these comrades. I used to think I had nothing to add to this discussion. It has already been said. But clearly it has not been heard, and it is not fair to sit back and cowardly leave the work to others. I realize that if medicine is to change, and really it must, then I –and others--must speak up in hopes of reaching a tipping point, when the old, paternalistic, reductionistic medicine, that looks for a quick fix in the form of a pill to solve every problem, makes way for a more self-empowering, holistic approach to medicine that recognizes the connections between mind, body, spirit and environment. A system that empowers patients with practical efficacious tools of self care and reimburses physicians to utilize the most powerful tools of their trade – time, listening, presence, compassion and hope in the context of a collaborative healing relationship.

Until that happens I will no longer remain a silent observer, but intend to keep writing and speaking up and I hope others will join the discussion.

Resources:

New England Journal of Medicine, Selective Publication of Antidepressant Trials and Its Influence on Apparent Efficacy, January 17, 2008 http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMsa065779#t=articleTop

JAMA, Emergency Department Visits by Adults for Psychiatric Medication Adverse Events, July 9, 2014

http://archpsyc.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1885708&utm_source=silverchair%20information%20systems&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=jamapsychiatry%3aonlinefirst07%2f09%2f2014

Huffington Post, New Research: Antidepressants Can Cause Long-Term Depression, November 16, 2011

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/dr-peter-breggin/antidepressants-long-term-depression_b_1077185.html

Psychological Side Effects of antidepressants worse than thought, University of Liverpool, February 25, 2014

http://www.psychcongress.com/article/psychological-side-effects-antidepressants-%E2%80%98alarmingly-common%E2%80%99-16173

http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2014-02/uol-pso022514.php

RSS Feed

RSS Feed